Professor Shimon Sakaguchi, Immunology Frontier Research Center

"A journey of curiosity and conviction - The story of Nobel laureate Professor Shimon Sakaguchi - "

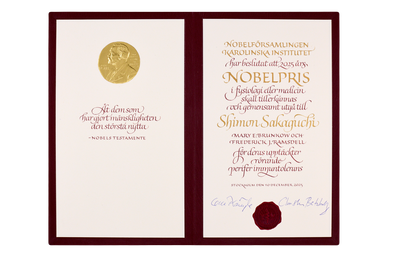

Professor Shimon Sakaguchi was awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize for his seminal discovery of regulatory T cells (Tregs), a crucial type of immune cell that maintains self-tolerance by preventing attacks on the body’s own tissues. Challenging prevailing theories, he first identified these cells in 1995. He later proved that the Foxp3 gene, discovered by his co-laureates, governs their development. This foundational work launched the field of peripheral tolerance, revolutionizing our understanding of autoimmune diseases and cancer, as well as the development of related therapies [1].

Diploma Shimon Sakaguchi 2025/Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs Book binder: Leonard Gustafssons Bokbinderi AB Photo reproduction: Dan Lepp © The Nobel Foundation 2025

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Clément Morin

Professor Shimon Sakaguchi graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at Kyoto University in 1976. In 1977, he became a research student in the Department of Experimental Pathology at the Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute. After obtaining his Ph.D. in medicine from Kyoto University in 1983, he served as a visiting researcher at Johns Hopkins University and later at Stanford University in 1987. He was appointed professor of molecular and cellular immunology at Kyoto University’s Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences in 1999 and later became the institute’s director. In 2011, he joined the Immunology Frontier Research Center (IFReC) at the University of Osaka as specially appointed professor of experimental immunology and was awarded the title of distinguished professor in 2017.

He is renowned for discovering regulatory T cells (Tregs) in 1995, a groundbreaking achievement often referred to as “the final major discovery in immunology,” and has since pursued research into the mechanisms of autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and the advancement of cancer immunotherapy.

An early fascination with immunology

I was raised in Nagahama, Shiga Prefecture. During junior high school, I belonged to the art club and was absorbed in drawing and sculpture. I dreamed of becoming an artist, but I eventually realized that I lacked sufficient talent in that field. In high school, I decided to become a medical doctor. Perhaps the influence came from my mother’s family, where a relative ran a local clinic, and through that connection, I may have cultivated an early sense of affinity for medical practice. Moreover, the works by physician writers, such as the German novelist Hans Carossa, also inspired me to pursue medicine.

Initially, upon entering university, I aspired to become a psychiatrist. However, at that time, psychiatry was closely aligned with the humanities, psychology or philosophy in particular. Although I diligently studied these subjects, I gradually lost interest. I found myself more drawn to medicine grounded in the natural sciences. My first encounter with immunology during a university lecture was transformative; I immediately felt a strong desire to explore it as my life’s research. I resolved that if the path of research did not suit me, I would return to clinical practice and serve as a medical doctor in my hometown. With that determination, I entered graduate school.

Finding a research path

In graduate school, I joined the pathology laboratory. However, its focus on phenomenological analysis offered little satisfaction for someone eager to elucidate the mechanisms of autoimmune disease through logical scientific inquiry. I began to question whether I should remain there. One day, while reading a medical journal, I came across an experimental report from the Aichi Cancer Center about thymectomy in mice.

T cells, which protect the body against viruses and bacteria, are produced in the thymus. Thus, removing the thymus should reduce lymphocytes and suppress immune reactions. Yet the experimental report described the opposite: the immune system began attacking the host’s own tissues. The phenomenon resembled human autoimmune diseases, and I sensed that a crucial mechanism lay hidden within it. Driven by this conviction, I withdrew from graduate school and requested to join Dr. Yasuaki Nishizuka’s laboratory at the Aichi Cancer Center as a research student.

Pursuing research in the United States

At that time in Japan, some studies on “suppressor T cells” were being conducted under a professor in Tokyo. Though these studies attracted considerable attention within the academic community, their relevance to autoimmune diseases remained unclear, and interest among researchers eventually faded. In contrast, what I observed at the Aichi Cancer Center was fundamentally different. When a mouse’s thymus was removed, it developed inflammatory responses attacking its own tissues; however, when T cells from the thymus of a normal mouse were transferred into the same animal, the inflammation subsided. This indicated the existence of a cell type that suppressed immune responses. Further analysis revealed that these cells expressed a surface antigen, CD4, distinguishing them from the so-called suppressor T cells.

I decided to continue my research in the United States. After returning to Kyoto University to complete my doctoral dissertation on “regulatory T cells,” which I had discovered, I earned my Ph.D. and entered Johns Hopkins University in 1983. However, I faced an unexpected obstacle: the controversy that had once surrounded suppressor T cells lingered as a negative legacy, and an atmosphere of skepticism toward the very existence of cells capable of suppressing immune responses had come to pervade the field of immunology.

From skepticism to recognition

At first, I felt entirely isolated in the U.S. Yet even under such circumstances, I managed to persevere without losing heart, thanks to the good fortune of receiving the Lucille P. Markey Biomedical Fellowship, a grant awarded to promising young researchers. Although most scientists at the time showed little interest in my work on regulatory T cells, the fellowship review committee found my research “fascinating,” and their recognition gave me both encouragement and stability, granting me research funding and a salary for eight years. I remain deeply grateful for the opportunity.

Another decisive change in fortune soon came when Dr. Ethan Shevach, a leading American immunologist whose research partially overlapped with mine, undertook a replication of my experiments. From that point onward, recognition of the existence of regulatory T cells began to grow gradually within the field. When Dr. Shevach—once a prominent critic of the suppressor T cell theory—dramatically reversed his position and expressed agreement with my reasoning, the shift was so striking that it was described within the immunological community as a “conversion.” This turning tide provided strong momentum, and following the publication of my 1995 paper, recognition of regulatory T cells increased significantly.

Harnessing Regulatory T Cells for therapeutic innovation

Autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and allergies to food or pollen all involve dysregulation of regulatory T cells. Patients with certain hereditary syndromes that exhibit a high incidence of autoimmune diseases, allergies, and inflammatory bowel disease have been shown to possess specific genetic abnormalities that prevent the proper generation of these regulatory T cells, which normally function to maintain immune self-tolerance. In simple terms, increasing regulatory T cells in the body can logically suppress excessive immune reactions—a principle now being tested in clinical trials for safety and efficacy.

Conversely, weakening or eliminating regulatory T cells could enhance immune activity against cancer. In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors—antibody-based drugs—have achieved remarkable advances in cancer therapy. By reducing the suppressive function of regulatory T cells and thereby amplifying autoimmune activity, we can potentiate the immune system’s attack on cancer cells. Thus, precise control over the number and function of regulatory T cells may hold the key to curing diseases once considered intractable. Based at IFReC, I continue my research, striving to contribute further to the advancement of medicine and human health.

Pursuing study and research until truly convinced

There is a quote from Dr. Hideki Yukawa, Japan’s first Nobel laureate, who said, “The essence of scholarship is to convince oneself.” I believe that without being convinced yourself, you cannot make progress in either study or research, nor will good ideas emerge. The quote truly captures the heart of this sentiment. Your motivation will never increase if you approach your work simply “because others are doing it” or “because it’s a popular trend.” I urge all high school and university students who aspire to become researchers to hold this conviction firmly and apply themselves with diligence every day.

At the same time, perseverance is crucial. Looking back on my own research career, it all began with a single question: “Why does the immune system attack the self instead of protecting it?” Pursuing that question for decades, accumulating results step by step, I have finally reached the stage where my work can contribute to clinical practice. While technology evolves, the spirit of embracing challenges remains timeless. There will be times of hardship, and you may find walls blocking your path. However, the true joy of research lies in moving forward with the belief that by accumulating small confirmations, you may pave the way for a great discovery. I encourage all of you to believe in the path you have chosen and keep moving forward.

Original text: https://www.ifrec.osaka-u.ac.jp/jpn/outline/docs/Imuneco_special_edition.pdf

[1] Press release. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. Thu. 30 Oct 2025. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2025/press-release/

Giving to Professor Sakaguchi’s research projects

Professor Sakaguchi’s pioneering work is paving the way for new treatments for autoimmune diseases and cancer. We invite your support to help his group continue and advance this life-saving research. Your donation will fund and accelerate vital research projects, train young scientists, and maintain our world-class facilities.